skip to main |

skip to sidebar

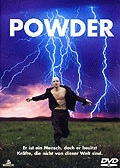

Copycats? Is there something intrinsic in the world of entertainment and creativity these days that causes people to eschew all attempts at originality and look to the Western world for ideas they can filch? I mean, look at some of the biggest releases in the Hindi film world in recent times - Fanaa, for instance, has been taken from Ken Follett's extremely well-written and gripping spy thriller, Eye of the Needle. Alag is a direct lift from the 1995 Hollywood film Powder, which starred Sean Patrick Flanery (see photographs above - note, especially, the similarity not only in the lead characters' appearances, but in their stances in the picture right at the bottom of the Alag poster, and that in the poster for Powder. Talk about dead ringers!) in the title role. Kaante, as everyone knows, was taken from Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs. What I don't understand is, first, why people in our country have to resort to plagiarism at the drop of a hat - and that too, do so without any compunction. Is it that we have a genuine dearth of good ideas in the so-called creative minds ruling the roost in our country? Or that these minds are just too lazy to exert themselves so as to come up with something original when it's so much easier to have someone else do the thinking and visualising, and just copy their end results?I tend to believe it's the latter - and here I'm not considering great film-makers like Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Shyam Benegal, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, but the ones churning out the mainstream Bollywood flicks. And somewhere, we tend to view this mindless copying as something laudatory. Just a couple of days ago, I read this gushing article on Rakesh Roshan's new film Krrish - and it was all about how the visual effects in this film are exactly like the ones in Hollywood films. India can finally make films whose visual appeal matches that of Hollywood, the writer stated proudly. And sure, we know that - all of us have been reminded inexorably of Neo (of Matrix fame) when we've caught sight of Hrithik Roshan in the film's trailers. I agree that the fact that we now have the technology to rival that of Hollywood is a source of pride - but why can we not put it to some original use? We've all seen the marvellous things American and British film-makers can do - how about finding out what the Indian ones can do with the same resources?And why do I say that we don't think there's anything wrong in plagiarising? Because I haven't yet come across anyone who's asked this question before. Because the same people who plagiarise with such impunity actually have the audacity to claim ownership - the Alag director, for instance, went on record telling the media how it's his special project, how a friend of his gave him the script and he loved it, how intense the whole experience of preparing the lead character's 'look' was - yeah, right! I mean, how intense could copying Sean Patrick Flanery's albino look have been? Though, of course, the well-muscled hero with the cool shades in Alag couldn't come even remotely close to capturing the vulnerability that Flanery brought to his performance (again, see the last picture of Flanery as Powder) - and no one, not even the film critics, ever slam them for it, not even when they calmly state in their reviews that such-and-such film was a rip-off from so-and-so. Remember what happened when the Kaavya (she of the plagiarised Opal Mehta fame) story broke? As someone in the publishing industry, I was extremely interested - I read every article, participated in discussions in forums, spoke to friends - and I was appalled by the fact that there was hardly anyone prepared to condemn her for her actions, or consider her culpable. Mitigating circumstances, everyone screeched, lack of ethics in the publishing world. All right, but what about her own ethics? She was old enough to know right from wrong - and there are mitigating circumstances in everyone's lives. Do we then make excuses for everyone who does something not quite right?Yet another example - last week HT City carried a story, complete with photographs, on how fashion photographers have been copying photos taken by photographers abroad for their calendars - so there was Bipasha Basu doing a J Lo, and Priyanka Chopra aping Britney Spears. And the photographers went a step further by actually claiming copyright for these pictures! I'm actually genuinely puzzled at this lethargic attitude and steadily declining originality in everything we do. Are we denegerating into a nation of copycats? And am I the only one, to quote the Dixie Chicks, who ever felt this way?

Copycats? Is there something intrinsic in the world of entertainment and creativity these days that causes people to eschew all attempts at originality and look to the Western world for ideas they can filch? I mean, look at some of the biggest releases in the Hindi film world in recent times - Fanaa, for instance, has been taken from Ken Follett's extremely well-written and gripping spy thriller, Eye of the Needle. Alag is a direct lift from the 1995 Hollywood film Powder, which starred Sean Patrick Flanery (see photographs above - note, especially, the similarity not only in the lead characters' appearances, but in their stances in the picture right at the bottom of the Alag poster, and that in the poster for Powder. Talk about dead ringers!) in the title role. Kaante, as everyone knows, was taken from Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs. What I don't understand is, first, why people in our country have to resort to plagiarism at the drop of a hat - and that too, do so without any compunction. Is it that we have a genuine dearth of good ideas in the so-called creative minds ruling the roost in our country? Or that these minds are just too lazy to exert themselves so as to come up with something original when it's so much easier to have someone else do the thinking and visualising, and just copy their end results?I tend to believe it's the latter - and here I'm not considering great film-makers like Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Shyam Benegal, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, but the ones churning out the mainstream Bollywood flicks. And somewhere, we tend to view this mindless copying as something laudatory. Just a couple of days ago, I read this gushing article on Rakesh Roshan's new film Krrish - and it was all about how the visual effects in this film are exactly like the ones in Hollywood films. India can finally make films whose visual appeal matches that of Hollywood, the writer stated proudly. And sure, we know that - all of us have been reminded inexorably of Neo (of Matrix fame) when we've caught sight of Hrithik Roshan in the film's trailers. I agree that the fact that we now have the technology to rival that of Hollywood is a source of pride - but why can we not put it to some original use? We've all seen the marvellous things American and British film-makers can do - how about finding out what the Indian ones can do with the same resources?And why do I say that we don't think there's anything wrong in plagiarising? Because I haven't yet come across anyone who's asked this question before. Because the same people who plagiarise with such impunity actually have the audacity to claim ownership - the Alag director, for instance, went on record telling the media how it's his special project, how a friend of his gave him the script and he loved it, how intense the whole experience of preparing the lead character's 'look' was - yeah, right! I mean, how intense could copying Sean Patrick Flanery's albino look have been? Though, of course, the well-muscled hero with the cool shades in Alag couldn't come even remotely close to capturing the vulnerability that Flanery brought to his performance (again, see the last picture of Flanery as Powder) - and no one, not even the film critics, ever slam them for it, not even when they calmly state in their reviews that such-and-such film was a rip-off from so-and-so. Remember what happened when the Kaavya (she of the plagiarised Opal Mehta fame) story broke? As someone in the publishing industry, I was extremely interested - I read every article, participated in discussions in forums, spoke to friends - and I was appalled by the fact that there was hardly anyone prepared to condemn her for her actions, or consider her culpable. Mitigating circumstances, everyone screeched, lack of ethics in the publishing world. All right, but what about her own ethics? She was old enough to know right from wrong - and there are mitigating circumstances in everyone's lives. Do we then make excuses for everyone who does something not quite right?Yet another example - last week HT City carried a story, complete with photographs, on how fashion photographers have been copying photos taken by photographers abroad for their calendars - so there was Bipasha Basu doing a J Lo, and Priyanka Chopra aping Britney Spears. And the photographers went a step further by actually claiming copyright for these pictures! I'm actually genuinely puzzled at this lethargic attitude and steadily declining originality in everything we do. Are we denegerating into a nation of copycats? And am I the only one, to quote the Dixie Chicks, who ever felt this way?

The Bookseller of KabulThis weekend I read Norwegian journalist Asne Seierstad's The Bookseller of Kabul, published in 2004, and subsequently reprinted no less than 25 times. It focuses on an Afghan family in the days immediately following the defeat of the Taliban by US forces - the family patriarch is the bookseller in question. The author looks at the lives, loves, hopes, desires and aspirations of the family members, and intersperses the account with dollops of Afghan history that anyone with the ability to trawl through Internet search engines can have access to. Shah Mohammad Rais (the bookseller, named Sultan Khan in the book) was so incensed after reading the book that he flew over to Norway with lawyer in tow, and sued Seierstad; they reportedly also got into trouble with the authorities and their neighbours. I can understand why.To begin with, the author makes up pseudonyms for everyone in question so as to maintain anonymity, but then describes them in such great detail, down to their professions and area they live in, that the entire exercise is rendered redundant. I'm also not sure why Seierstad chose this particular family - as she herself claims in the Foreword, the family, being an urban, educated, rich one, isn't representative of Afghan families at all. As an author, she is well within her rights to choose the story she wants to tell, and focus on characters that are best suited to take the narrative forward - but if the story is a true one, and the characters real people, holding them up to the world's scrutiny without any well-defined rationale can just be a mere exercise in voyuerism. Which, to my mind, is what this book is all about. Coupled with this is the trap all white, Western people fall into - that of gazing at the 'other', the developed nations, through their detached, culturally-specific, and all too often ill-equipped lenses, and interpreting cultural nuances with their aid. In her attempt to fit Afghanistan within the stereotypical vision that most people outside the country, especially those from the global North, have of it, the author highlights only those incidents that conform to the stereotype, and focuses on just that evidence that confirms her hypothesis - that Afghanistan is a backward country still in the grip of religious forces, where men rule and women are treated worse than cattle. All of which might well be true, but is a journalist really allowed to choose only those facts that best suit her at any given moment in time? There's a thin line between reporting on another culture and using the facts to reflect your own bias - The Bookseller of Kabul is an indictment of Afghan society in general and this one family in particular. Seierstad stayed with the Rais family for several months - I cannot believe that in all these months she came across just these smattering of incidents to write about. As a white woman, her primary concern was the way 'women were treated' - a fact that's not new to any of us in the Indian subcontinent, but which must have elicited gasps of horror from the so-called progressive white world - the target audience. While Sultan Khan is held up as a man brave enough to defy the Taliban and court imprisonment in an attempt to preserve his country's history and culture, that facet of his personality is subsumed under detailed descriptions of his despotic behaviour towards the rest of his family, his lasciviousness where his beautiful, teenaged second wife was concerned, his materialistic bent of mind that caused him to sacrifice humanity at the altar of business and profits. We get to hear all about how his sons hate him (has anyone who read the book notice how peculiarly ambivalent her attitude towards Mansur was? Was she sympathetic or did she disapprove of his selfishness? Was Mansur a confused teenager whose will was steadily being eroded by his tyrannical father, or was he a spoilt, self-centred boy who believed everyone in the world had been created for his pleasure alone? He took on several guises, much in the manner of a chameleon, depending on the point the author was driving home at that given moment) and the women in his family fear him - all helpfully repeated with every anecdote just in case you missed the point the first, second, or fifth time.My major problem with the book is that it adds nothing to our knowledge about Afghan history or culture - as I mentioned earlier, the bits of history the author rather monotonously recites are stuff we all know about, or facts easily available on the Internet. There is no analysis, no critical commentary - just a mere presentation of facts, whether they be about the history of Afghanistan, or about the Rais family. However, how is getting to know the little domestic details of one family in Afghanistan going to help anyone? How is it enriching the corpus of literature that already exists on this topic, and sundry related others? The only thing it does it satiate our desire to see into other families, to satisfy the voyeur present in all of us. Seierstad doesn't disappoint here. She lingers deliciously (much like the Afghan women she describes gossiping) on stories of young women's transgressions in matters of love, and the punishment that befell them thereafter; on the 'dirty thoughts' that flit across the minds of young teenage boys; and, most obviously, in the whole chapter devoted to the hammam. Now, all of us with some knowledge of the world know what the hammam is all about. It's no different from the bathhouses of Rome, or the saunas in the West. It's a communal bathing area. Fatima Mernissi and Bouhidiba, among others, have written marvellous articles critically analysing the role of the hammam in Islam, and the gender relations that become manifest through it. That, however, is not what Seierstad had in mind - she chooses to focus on the hot and steamy interior, scenes of women scrubbing each other's backs, breasts and thighs, talk about how married women strip completely while unmarried ones don't - if this isn't blatant voyeurism, what is? I'm not surprised Mohammad Rais was furious. Instead of a book on his family he could proudly show off, he was presented with constant references to his cruel and tyrannical character, accounts of his family's alleged feelings towards him as well as their illicit desires, all of which he would rather not have known, and, as if that wasn't enough, he had to be presented with rather negative descriptions of the naked body of his mother! If that's not going to drive a traditional, god-fearing, conservative man to apoplexy, I don't know what is. Would Seierstad have done the same with the mother of, say, a bookshop owner in Soho?Seierstad, in every work of hers, is annoyingly self-indulgent, a fact her next book, 101 Days, an account of the first 100 days of the American war on Iraq, attests to. Unlike most good journalists, she focuses more on herself than the history she's witnessing, or the people she's interviewing, or even the facts she's reporting. We can't but be aware of her presence throughout - and nowhere is it more obvious than in The Bookseller of Kabul. Cliched, pointless and badly-written, Seierstad's work is a lesson on how journalism ought not to be done. I'm not surprised it became a bestseller, though - after all, the same can be said of The Da Vinci Code, and look where that's at now. Also, there's nothing people like more than to witness someone else's dirty linen being washed in public.I'd initially intended for this blog to contain short reviews of three books, but this one seems to have taken up way too much space already. So will leave the others for later blogs - and the remaining two, thankfully, have been books I enjoyed immensely.